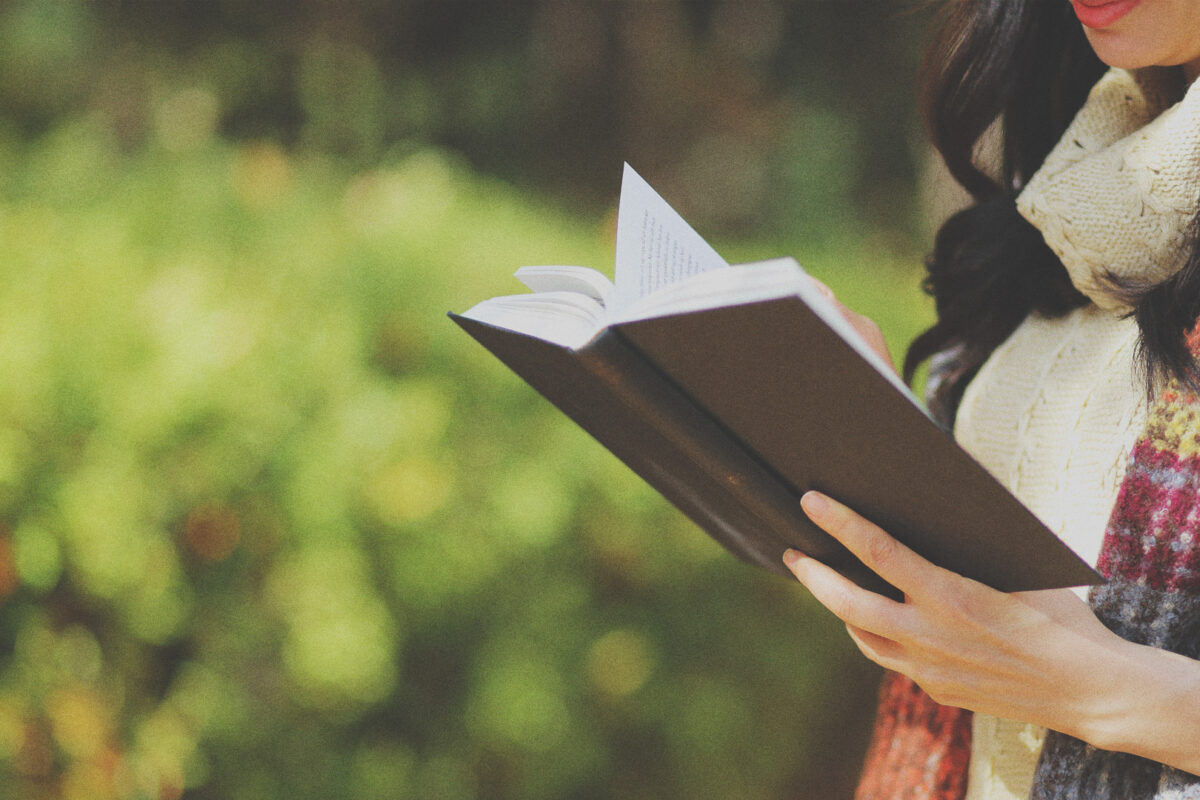

What your brain does when you crack that summer novel

Even if you don’t consider yourself a “reader,” you read all the time. Signs, instructions, articles, bills, blogs, newspaper headlines and grocery lists all depend on literacy. Literature is the icing on the cake. Reading permeates so much of our lives, and yet human civilization has only been literate for a tiny sliver of our history.

Ancient texts suggest that writing and reading had already been developed in Mesopotamia roughly 5,000 years ago, but it is only in the last 300 years that literacy rates have skyrocketed. Why did it take thousands of years to bring reading to the masses?

Put simply, our brains were not made to read.

The reading brain

Most of us have forgotten the work we put into learning to read because, once learned, the practice is natural and automatic. So automatic, in fact, that it is nearly impossible not to read when you look at a familiar word.

As children, reading is far from automatic. We all spent hours with Mrs. D and Mr. P. We sang the ABC song while we were learning to count. We had books read to us before we could speak. Our most important tasks, for years, included sounding out words, spelling, and mastering increasingly complex reading tasks.

We spent all this time learning and practicing because the capacity to read is not a native feature of the human brain. Intensive training created complex connections that otherwise would not exist. Today, modern tools have given us a glimpse into the permanent changes we create in our brains when we learn to read.

EEG explorations

An EEG reading is a visual representation of your mind’s electric orchestra. Key notes, or high-volume evidence of inter-related activity in response to sensory inputs, are called event-related potentials (ERPs). Though analysing EEG results and identifying the mechanisms at work in ERP is a tricky business, a 2009 study delves into the electric brain patterns of reading.

The study looks specifically at word recognition, an essential component of reading, and finds that this seemingly simple process includes at least three ERP. First, you need to see the word. Cue visual cortex. Next, you need to apply an understanding of how words work. (In what order are letters read? What is spelling?) Enter sublexical orthographic coding. Finally, you need to map this understanding to the word at hand using phonology. These distinct activities, researchers believe, make up the three ERP identified in the EEG signals of reading.

Bottom line: Word recognition is incredibly complex.

MRI activation findings

Beyond brainwaves, researchers are interested in which parts of the brain are activated in reading. This is especially important in identifying the neurological basis of learning disabilities like dyslexia, a language-based learning disability that impacts roughly 10 percent of people.

A 2014 study comparing the brains of non-impaired readers to dyslexic readers found differing patterns of activity. Non-impaired readers had strong activation in posterior regions of the brain and weaker activation in an anterior region called Broca’s Area. Dyslexic readers showed the opposite pattern of activation. Broca’s Area has been most strongly associated with speech, not reading, which might explain why dyslexia impairs reading skills.

Researchers believe that the posterior regions are important for connecting sounds to letters and making automatic phonetic connections, precisely the tasks where dyslexic readers struggle. Though we aren’t certain of the reason for overactivation in Broca’s area, it wouldn’t be the first example of a brain compensating for one weakness by relying on alternative strengths.

Structural evidence of reading

Scientists have also found that reading changes the very structure of your brain. In a 2018 study of 21 children, researchers measured word reading fluency and sentence comprehension. They then compared proficiency in these skills to cortical thickness. They found proficiency in word reading correlated with increased thickness in four distinct parts of the brain. Thickness was observed in two other parts of the brain in correlation with superior sentence comprehension.

Equally interesting, researchers were able to predict proficiency in phonetic representation, phonological awareness, and orthography-phonology mapping skills by looking at the cortical thickness of respectively associated brain regions.

Beyond reading

Reading is an essential ingredient in our great success as a species. It has allowed information sharing on a historically unparalleled scale. Complex invention, collaboration, and technology are all supported by the written word. Though correlation doesn’t equate to causation, our advances as a species have evolved in parallel to our ability to read.

Harvard University neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf has a theory. Not only were we “never meant to read,” but reading has initiated a man-made evolution of the human brain. Given the studies documenting very real changes that occur in our brains when we learn to read, science appears to agree with her. If the last 300 years are any estimation of our future evolution as a species, the future is looking wordy – and bright!

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.